Supreme Court Learning Center Timeline Key Questions? Contact: Samuel Wheeler, 618-201-7343, Samuel.Wheeler@IllinoisCourtHistory.org

1818 = Kaskaskia served as Illinois’s first state capital from 1818-1819. The Illinois Constitution of 1818 established the state’s Supreme Court, initially composed of four justices, who were appointed by the General Assembly. At that time, the legislative branch held the majority of political power in Illinois, and justices were often politically active, viewing their appointments as steppingstones to higher office. The Illinois Supreme Court met for the first time in July 1819 in the statehouse in Kaskskia (pictured), hearing a few cases that were carried over from the territorial period. In 1820, the state capital moved to Vandalia, where the Court continued to meet until 1839, when the capital was relocated once more, this time to Springfield. Throughout Illinois history, the state has operated under four constitutions (1818, 1848, 1870, and 1970), each of which has significantly influenced the structure and composition of the Illinois Supreme Court.

1840 = Under Illinois’s first constitution of 1818, the Illinois Supreme Court was composed of four justices who were not elected by the people but appointed by the Illinois General Assembly. By 1840, the Democratic Party controlled both the legislature and the governor’s office, yet three of the four justices on the state’s highest court were aligned with the Whig Party. Concerned that the Court was hostile to their political interests, Democrats sought to reshape the judiciary. In 1841, Stephen A. Douglas, a rising star in Illinois politics and a leading figure in the Democratic Party, spearheaded a controversial bill to expand the Illinois Supreme Court from four to nine justices. This legislation, passed by the Illinois General Assembly, allowed the Democrat-controlled legislature to appoint five new justices, all loyal to the Democratic Party. As a result, the Democrats secured a majority on the Court, effectively neutralizing Whig influence. This political maneuver highlights the lack of judicial independence during the early years of Illinois statehood. Although the state’s constitution emphasized the principle of three co-equal branches of government, it would take decades for this ideal to fully materialize. Judicial independence—a cornerstone of modern democratic governance—was still in its infancy in the first decades of statehood.

1845 = The Jarrot Mansion in Cahokia, Illinois, is historically significant for its connection to the landmark Illinois Supreme Court case Jarrot v. Jarrot, which ended chattel slavery in the state. Slavery was introduced to the Illinois Country by the French in the 17th Century. It persisted under British rule (1763-1783) and continued during the period when Illinois was a territory (1783-1818). Although the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in the region, the French were allowed to keep their slaves in Illinois and slavery under the guise of “voluntary servitude” continued. When Illinois joined the Union in 1818 as a “free state,” its first constitution declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall hereafter be introduced into the state.” However, the term “hereafter” was interpreted to mean that individuals already enslaved or indentured would retain their unfree status. In the early decades of statehood, anti-slavery advocates used the legal system to bring about change. In 1843 Lyman Trumbull filed a suit on behalf of Joseph Jarrot, a slave in St. Clair County, against his owner for back pay. Trumbull argued that, according to the Northwest Ordinance, slavery should have been abolished prior to statehood, and if it had been, Joseph was entitled to compensation for his labor. The St. Clair County Circuit Court ruled against Joseph. Trumbull appealed the verdict, and in 1845, the Illinois Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s decision with a 6-3 ruling. The Court declared that descendants of former French slaves could not be held in slavery in Illinois, due to both the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the Illinois Constitution. Joseph Jarrot and others in similar situations were granted their freedom. The case effectively ended chattel slavery in Illinois. The second Illinois Constitution, adopted in 1848, outlawed the controversial “voluntary servitude” system that had been in place since the territorial period.

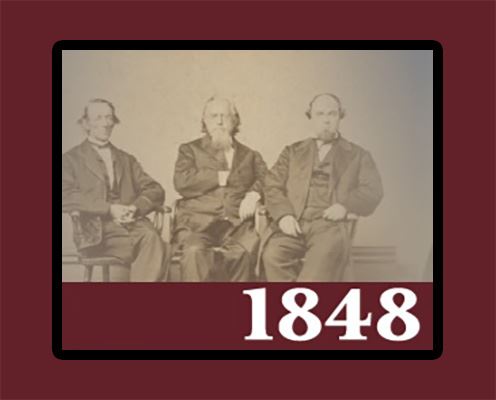

1848 = Illinois’s second constitution, enacted in 1848, significantly reshaped the state’s Supreme Court. Most notably, it called for justices to be popularly elected, instead of being appointed by the legislature. The new constitution reduced the number of justices from nine to three, each serving a nine-year term. It also introduced a system of geographic representation by dividing the state into three grand divisions—Northern, Central, and Southern. Each region was responsible for electing its own justice. The Court convened annually in each of these grand divisions, meeting in Ottawa, Springfield, and Mt. Vernon, a practice that continued until 1897. The constitutional changes resulted in more qualified lawyers, rather than political opportunists, occupying seats on the Illinois Supreme Court. In addition, the Court experienced a lower turnover rate among justices. Gradually, the Court began to establish itself as an important component of state government, with increasing levels of judicial independence. This image represents the first photograph of the members of the Illinois Supreme Court. Taken sometime between 1864 and 1870, the members are, from left to right: Charles Lawrence, Sidney Breese, and Pinkney Walker.

1855 = Lyman Trumbull (left) was one of Illinois’s most prominent anti-slavery advocates. As a lawyer, his greatest victory came in 1845 with the case of Jarrot v. Jarrot, which effectively ended chattel slavery in Illinois. As a politician, he is best remembered for authoring the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which forever outlawed American Slavery in 1865. Trumbull served as a justice on the Illinois Supreme Court. He was elected in 1848, under the new Constitution, but resigned in 1853 to pursue political ambitions. He split with the Democratic Party over Stephen A. Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” stance on the slavery question. In 1855 he became a U.S. Senator, a position he retained until 1873. During the Civil War, Senator Trumbull chaired the powerful Judiciary Committee and played a critical role in authoring significant legislation. He was instrumental in passing the Confiscation Acts, which pushed President Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Abraham Lincoln (right). Though Abraham Lincoln never practiced law in this building— dedicated 43 years after his death—his legacy looms large. During his 23-year legal career, Lincoln and his law partners were involved in more than 400 cases before the Illinois Supreme Court. One of his most notable appellate cases was Illinois Central Railroad v. McLean County (1855). In this case, Lincoln successfully argued that the 1851 statute establishing the Illinois Central Railroad was constitutional, specifically its provision exempting the railroad from paying taxes in lieu of giving the state 7% of its profits. The case saved the railroad millions of dollars, allowing it to flourish for more than a century. Interestingly, Lincoln was forced to sue the Illinois Central Railroad, his own client, to collect his $5,000 legal fee for the case.

1869 = Myra Bradwell (left) attempted to become the first woman licensed to practice law in Illinois in 1869. Her application was denied by the Illinois Supreme Court, which cited the common law principle of coverture, which held that a married woman could not enter into contracts, including attorney-client agreements. Although Bradwell argued that many of these restrictions had been lifted, the Court denied her admission based solely on her gender. Her appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was unsuccessful. Alta Hulett (right), an aspiring attorney and Bradwell’s contemporary, played a critical role in advocating for women’s rights. Alongside Bradwell, Hulett lobbied for legislation that would grant women access to the legal profession. Their efforts led to the passage of groundbreaking legislation allowing women to practice law in Illinois. In 1873, Hulett became the first woman licensed to practice law in the state, achieving this at the age of 19, making her the youngest attorney in Illinois history. At that time, men could not be licensed until the age of 21, the age of majority, whereas the age of majority for women was 18. In 1890, the Illinois Supreme Court retroactively granted Bradwell her law license from 1869, though she never practiced. Though progress was slow, the efforts of Bradwell and Hulett paved the way for future generations. In 1992 Mary Ann McMorrow became the first woman elected to the Illinois Supreme Court and in 2002, she made history again by becoming the first female Chief Justice of the Illinois Supreme Court. In 2022, for the first time in Illinois history, the Illinois Supreme Court became majority female. Today, more than half of all law students in the US are women, and more than 86% of law schools in the US have more female than male students.

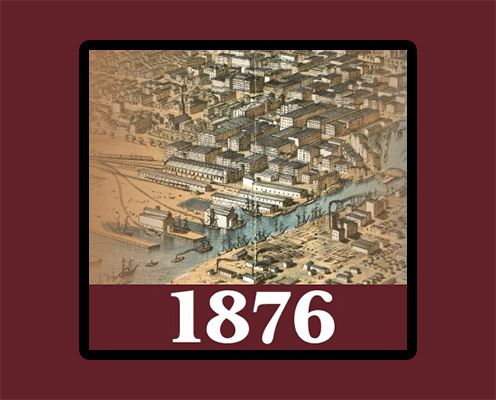

1876 = The case of Munn v. Illinois resulted in a landmark decision handed down by the Illinois Supreme Court that established the precedent for government regulation of public utilities. This map (pictured) highlights the grain elevators along the Chicago River. Midwestern grain farmers relied on these elevators to store their grain until it could be sold and transported to buyers in other states. Munn and Scott, a firm founded in 1862, grew to dominate the grain storage industry in Chicago, controlling the rates charged to farmers. In 1871, the Illinois General Assembly enacted a law to limit the prices that grain elevators could charge, aiming to address complaints from farmers about excessive fees. When Munn and Scott refused to comply with the new pricing regulations, the state initiated legal action. When the lower court ruled against Munn and Scott, they appealed. The Illinois Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision. The Court ruled that the state had the authority to regulate the prices charged by private businesses when those businesses served a “public interest” or a “common good.” The decision was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which also affirmed the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling. Munn v. Illinois is considered one of the most influential cases to emerge from Illinois because it affirmed the government’s right to regulate public utilities. This decision has since formed the basis for both state and federal regulatory practices, underscoring the government’s role in overseeing industries that serve the public interest.

1886 = The Haymarket Riot occurred in Chicago on May 4, 1886, during a labor demonstration advocating for an eight-hour workday. The demonstration turned violent when an unknown person threw a bomb into a group of police officers, killing seven and injuring dozens. In the chaotic aftermath, hundreds were arrested, two anarchist newspapers were shut down, and Chicago fell into near martial law for eight weeks. The event sparked the nation’s first “Red Scare,” with widespread suspicion cast on Chicago’s large immigrant population—particularly Germans and anyone associated with leftist ideology or labor movements. Though it was never determined who threw the bomb, eight anarchists and socialists—five of whom were German immigrants—were charged. The prosecution argued that their inflammatory writings and speeches prior to the event incited the violence. Even though they were not directly involved in the bombing or, in some cases, even present when it occurred, the court found them guilty of conspiracy. Seven defendants were sentenced to death, while one received a 15-year prison term. Labor organizations around the world condemned the harsh verdict. In 1887 the case, Spies v. Illinois was appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court. The Court upheld the convictions, focusing on the defendants’ previous actions, speeches, and writings that encouraged workers to revolt, along with references to bomb-making in their publications. Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby commuted two of the sentences to life imprisonment, while one defendant committed suicide before the scheduled execution. On November 11, 1887, four of the condemned men were hanged. In 1893 Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the remaining defendants, sharply criticizing the fairness of the original trial and the judicial process that led to their convictions and executions.

1896 = Labor Laws for Women and Children. In the early 1890s, Florence Kelley, a prominent Hull House activist and Illinois factory inspector, championed the passage of labor laws aimed at protecting women and children. Her efforts resulted in legislation that limited women to eight-hour workdays and established working-age restrictions for children. However, the new law was soon challenged by William Ritchie, a paper box manufacturer in Chicago, who was indicted for violating it. Ritchie argued that the law infringed on his rights as a business owner. In 1895 the Illinois Supreme Court agreed with him, ruling the law unconstitutional and reaffirming the rights of workers to freely contract their labor without state interference. Despite this setback, reformers continued their fight. In 1909, the Illinois legislature passed a revised law that restricted women’s workdays to ten hours. Once again, Ritchie challenged the law. Famed attorney Louis Brandeis presented his “Brandeis Brief” to the Illinois Supreme Court. Unlike traditional legal arguments, Brandeis incorporated extensive sociological data, alongside legal reasoning, to argue that limiting work hours for women was a critical matter of public health and welfare. The Illinois Supreme Court declared the ten-hour day law to be constitutional, successfully limiting the working hours of women and children.

1899 = The Illinois Juvenile Court was a groundbreaking development in the U.S. justice system, created by social reformers Julia Lathrop and Jane Addams. Located across the street from Hull House, the court was established following the passage of the Illinois Juvenile Court Act in 1899, which created the nation's first juvenile court in Cook County. This act served as a model for similar courts across the U.S. and worldwide. Before 1899, all individuals over the age of seven were treated the same in the legal system, facing identical charges, incarceration, and punishment as adults. Progressive reformers believed minors deserved a separate judicial process focused on rehabilitation, rather than punitive measures. They lobbied the Illinois General Assembly, and on July 3, 1899, the Illinois Juvenile Court Act took effect, establishing a new legal system for children under 16. The Juvenile Court Act sought to remove the stigma of criminality from children by making the proceedings confidential and informal. Traditional legal elements like complaints or indictments were replaced with petitions, and warrants were replaced by summonses. Children were not arrested but brought to court by a parent, guardian, or probation officer. The act also prohibited detaining minors in jails where adults were held. The focus was on rehabilitation rather than punishment. Probation officers were tasked with representing the child's best interests, and sentences aimed to place children in the care of probation officers or supportive institutions instead of reformatories or prisons. Proceedings were intentionally informal, allowing for a more humane approach to juvenile justice. Although the Illinois Juvenile Court was a pioneering institution, its results were mixed. Critics pointed out that the court primarily dealt with low-income and immigrant children and applied gender biases in its rulings. For instance, boys were more frequently sent to reformatories, while girls were predominantly treated for "morality" infractions. Despite these shortcomings, the Illinois Juvenile Court set the foundation for future juvenile justice reforms.

1899 = Ferdinand Barnett was one of the most prominent African American attorneys in Illinois during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born a slave in Nashville, Tennessee, Barnett’s father purchased his family’s freedom. They moved to Canada before the Civil War and then to Chicago in 1869. Barnett attended Union College of Law (now Northwestern Law School), and in 1878, he became the third African American admitted to the Illinois bar. In addition to practicing law, Barnett founded Chicago’s first African American newspaper, The Conservator. Through the publication, he championed civil rights, addressed issues like racial segregation, voting rights, and discrimination, and advocated for the racial integration of the public school system. In 1897, Barnett made history when he was appointed assistant’s state’s attorney in Cook County, becoming the first African American to hold the position in Illinois. During his 10-year tenure, Barnett handled nearly 30 cases before the Illinois Supreme Court. In 1895, Barnett married Ida B. Wells, the renowned anti-lynching activist. Together, they used their newspaper and the legal system to fight for civil rights, advocating for the advancement of African Americans throughout the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras.

1907 = Catharine Waugh McCulloch was a pioneering figure in the fight for women’s suffrage, but she also achieved a historic milestone in 1907, when she became the first woman in Illinois to serve in a judicial capacity. Waugh McCulloch graduated from Union College of Law in 1886. She practiced law in Rockford before moving to Chicago to practice with her husband. Waugh McCulloch ran for justice of the peace in Evanston in 1907 and defeated her opponent handily, becoming the first woman in Illinois history elected to a judicial position. At her first session as justice of the peace, several men asked her if she needed help. She replied, “I do appreciate the courtesy of my friends so much, but I don’t see why there is so much interest in this. I’ve studied law, you know.” While Justice of the Peace, she made national headlines by agreeing to conduct egalitarian marriage ceremonies that omitted the word “obey” from the words a woman was supposed to say. Throughout the rest of her career, she worked to eliminate or modify marriage and divorce laws that discriminated against women. In addition to transforming women’s roles in the Illinois judiciary, Waugh McCulloch fought for women’s suffrage. When the Illinois Supreme Court upheld a law granting women the right to vote in school district elections in 1891, she worked on a bill that would allow Illinois women to vote in local and presidential elections. In 1913 the Illinois legislature passed a bill that allowed women to vote in presidential elections—making Illinois the first state east of the Mississippi River to do so. However, Illinois women could still not vote in statewide elections, as that would require an amendment to the state’s constitution.

1908 = Dedicated on February 4, 1908, the Illinois Supreme Court Building in Springfield serves as the permanent home of the state’s highest court. For the first 90 years of statehood, the court met in various locations, including Kaskaskia, Vandalia, Ottawa, Mount Vernon, and at several locations in Springfield. In 1897, however, the Illinois legislature consolidated the court’s operations to Springfield, but the Court quickly outgrew its quarters in the statehouse. In 1905, Illinois Senator Corbus P. Gardner introduced Senate Bill 469 to construct a building dedicated to the Illinois Department of Justice. The bill passed and the governor signed it into law on May 18, 1905. The Supreme Court Building Commission was created to oversee the project, with a total appropriation of $450,000. A design competition open to Illinois architects resulted in William Carbys Zimmerman, the state architect, submitting the only design. The Peoria firm of V. Jobst & Sons was awarded the construction contract, and the cornerstone was laid on December 20, 1906. The neoclassical building, inspired by the U.S. Treasury Building in Washington, D.C. and the Pantheon in Rome, features three stories and a full basement. The first floor was devoted for use by the Attorney General’s Office and court clerks. The second floor included the Supreme Court courtroom and a large conference room, attorney’s room, the Appellate Court courtroom and its separate conference room, and the law library. The third floor included private apartments for seven Supreme Court justices and the three Appellate Court judges. Artists were commissioned to decorate the interior and exterior of the building: Albert H. Krehbiel painted 13 murals for the courtrooms, Charles J. Mulligan created two exterior sculptures, and Edgar Spier Cameron painted four murals in the law library. In 2013 the building underwent a year-long restoration, including new HVAC systems and updates to mechanical, electrical, and plumbing infrastructure. The interior was returned to its original colors, and the murals were cleaned. Today, the building resembles its 1908 appearance. In 2023, the Illinois Supreme Court added a Learning Center in what was once the Appellate Court conference room.

1914 = Women and the right to vote. 2020 marked the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which prohibited federal and state governments from denying the right to vote based on gender. While the movement was national, Illinois played a key role in securing women's suffrage. Women's suffrage in Illinois was intertwined with the abolition and temperance movements before the Civil War. Arguments against women voting were rooted in laws of coverture, which merged a married woman’s legal identity with her husband’s, preventing her from entering into contracts, suing, or owning property independently. The Illinois legislature began to address these issues with the Married Women Property Act of 1861, which allowed married women to own real estate and marked the beginning of legal reforms leading up to the suffrage amendment. The first woman to vote in Illinois was Ellen Martin on April 6, 1891. A Chicago attorney living in Lombard, Martin cast her ballot following the incorporation statute of Lombard, which permitted all citizens over 21 to vote. Though election officials were surprised to see a woman at the polls, she successfully encouraged 14 additional women to vote that day. Opponents of suffrage argued that men earned income while women managed households. Suffragists countered that if women were responsible for children and homes, they should have a say in related elections. In May 1891, Illinois granted women the right to vote in school elections, which was upheld by the Illinois Supreme Court. In 1913, Illinois became the first state east of the Mississippi River to allow women to vote in presidential elections, a decision affirmed by the Illinois Supreme Court in 1914. Despite this victory, women were still not allowed to vote in state elections, since that would require an amendment to the Illinois Constitution. World War I heightened awareness of women’s societal contributions. In response, the U.S. Congress passed the 19th Amendment in May 1919. Illinois ratified it on June 10, becoming the first state to do so, although a typo in transmission papers led Wisconsin to later claim the title of first state to ratify the amendment. On August 18, 1920, following Tennessee’s ratification vote, the amendment became law, granting women the right to vote nationwide.

1920 = Clarence Darrow is widely regarded as one of the most famous attorneys in American history. His high-profile cases, including the defense of Eugene V. Debs, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, and John T. Scopes, during the famous Scopes “Monkey Trial,” where he opposed William Jennings Bryan, earned him considerable fame and fortune. Based in Chicago, Darrow was known for his vigorous defense work and staunch opposition to the death penalty. Of the more than 100 capital murder cases he handled, only one of his clients was executed. He was also an active member of the American Civil Liberties Union. Between 1891 and 1936 Darrow argued at least 18 cases before the Illinois Supreme Court. These included one argument in Ottawa during the Court’s Northern Grand Division sessions, five arguments took place in the Illinois Capitol Building in Springfield, and 12 occurred in this building.

1940 = Lorraine Hansberry was seven years old when her family moved to the Washington Park neighborhood on the South side of Chicago. Two decades later, she wrote the acclaimed Broadway play, “A Raisin in the Sun,” based on her family’s legal struggles with housing discrimination in Chicago. Carl Hansberry moved to Chicago as a young man during the Great Migration, a period in which African Americans relocated to northern cities to escape racial violence and seek economic opportunities. Many like Hansberry settled their families on the south side of Chicago. To prevent African Americans from moving into certain neighborhoods, residents of all-white areas often used restrictive covenants. In Washington Park, a restrictive covenant stated that “no part of the property restricted should be sold to, leased to, or permitted to be occupied by any person of the colored race.” This covenant required the signatures of 95% of the neighborhood’s residents, but only 54% agreed. The Hansberrys moved to the neighborhood in 1937. Anna Lee, a resident, sued Carl Hansberry to enforce the covenant. The Cook County Circuit Court ruled in favor of Lee, citing a previous case that upheld similar covenants. Hansberry appealed the decision to the Illinois Supreme Court in Lee et al. v. Hansberry (1939), which affirmed the lower court’s judgment. However, Hansberry took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling. In a unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the Illinois Court’s decision violated Hansberry’s due process rights under the 14th Amendment. Eight years later, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a broader ruling that ended the judicial enforcement of racial covenants. Loraine Hansberry later moved to New York City and became a prominent writer. Her play, “A Raisin in the Sun,” reflected her family’s legal struggles with racial covenants. It was groundbreaking as the first Broadway play produced by an African American woman. Hansberry died in 1965, three years before the passage of the Fair Housing Act, part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

1942 = Parking Meter Case. The Illinois Supreme Court hears a wide range of cases, both large and small, that affect our everyday lives. For example, during World War II, the Court had to decide if cities could legally install parking meters that required motorists to pay for parking on city streets. In 1942 Roy Wirrick received a parking ticket in Bloomington, Illinois, for failing to deposit a nickel into a five-cent parking meter. He challenged the ticket. In City of Bloomington v. Wirrick, he argued that public streets should be free and open for taxpayers to park without charge. He claimed his constitutional rights were violated when the city installed parking meters that required payment for parking. The case eventually reached the Illinois Supreme Court, which ruled that parking meters are constitutional under Illinois law. Wirrick then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but his petition was denied. As recently as 2013, the Illinois Appellate Court cited this decision to reaffirm that municipalities have the authority to regulate parking on public streets.

1947 = Vashti McCollum, an atheist living in Champaign, Illinois, sued the public school district in 1947 for allowing religious education classes in public school. Her son James attended public school where religious education classes were offered during regular school hours. The classes, organized by religious groups, were held on school property. Students were either required to attend or be segregated if they opted out. McCollum objected to her son being pressured to participate in these classes. She argued that the practice violated the principle of separation of church and state. However, the Champaign County Circuit Court ruled against her, and she lost again when she appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court. McCollum appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In the landmark McCollum v. Board of Education (1948) decision, the U.S. Supreme Court, in an 8-1 decision, declared that religious education classes at public school were unconstitutional. The court found that using taxpayer-supported public school facilities to promote religious education violated the principle of separation of church and state. Although the decision was controversial at the time, it has been cited in subsequent rulings on issues such as school prayer, Bible reading, and other religious activities in public schools.

1980 = Capital Punishment. Illinois had a death penalty since it operated under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, and it maintained the practice after achieving statehood. According to the state’s first criminal code in 1819, death was the mandatory punishment for murder. Reports indicate that Illinois has executed at least 360 people, including August Spies (1887), a leader in the Haymarket Riot, Charlie Birger (1928), a gang leader in southern Illinois, and John Wayne Gacy (1994), a serial killer. However, Illinois has also had many outspoken opponents of capital punishment, including famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow and Progressive reformer Jane Addams. Illinois Supreme Court Justice Seymour Simon, 1980-1988, (pictured) was one of the most effective critics of the death penalty, deeming it unconstitutional in his written opinions. In at least 26 cases, Justice Simon dissented whenever the court affirmed a death sentence. After retiring from the bench, Simon continued advocating for the end of capital punishment. He advised Illinois Governor George Ryan, arguing that the death penalty could not be imposed fairly or uniformly due to the lack of sufficient standards guiding the 102 state’s attorneys in deciding when to pursue it. In 2000, Governor Ryan declared a moratorium on executions after 13 people on death row were exonerated, highlighting flaws in the system. In 2011 Governor Pat Quinn signed legislation making Illinois the 16th state to abolish the death penalty. Today, capital punishment is outlawed in 23 states.

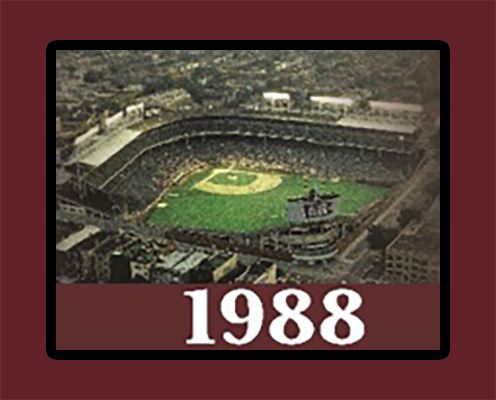

1988 = More than fifty years after the first night game in Major League Baseball, lights finally came to Wrigley Field, home of the Chicago Cubs. Phillip Wrigley, longtime Cubs owner, resisted bringing night baseball to Wrigley Field for decades. The residents of Lakeview, the neighborhood surrounding the ballpark, were concerned that night games would bring nuisances like excessive noise, public drunkenness, and increased vandalism. However, in 1981 the Tribune Company purchased the Cubs and began exploring the possibility of installing lights for night games. Almost immediately, a new community group, Citizens United for Baseball in Sunshine (C.U.B.S.) emerged to oppose the idea, warning that night games would be detrimental to the neighborhood. The group successfully lobbied the Illinois General Assembly and the Chicago City Council to pass legislation that effectively barred night baseball at Wrigley Field. In response, the Cubs’ new owners protested the bans, threatening to relocate the team to a new stadium if a compromise could not be reached. They also appealed to the legal system, arguing that the state and local laws singled out the Cubs, as every other MLB team played night games. In 1985, the issue reached the Illinois Supreme Court, which ruled against the Cubs owners, stating that the state and local laws against night games were reasonable uses of government power and did not unfairly discriminate against the Cubs. Despite the legal setbacks, night baseball finally came to Wrigley Field in 1988, after the Chicago City Council amended local ordinances. The Cubs agreed to a limited night game schedule for that season. The first night game, scheduled for August 8, 1988 (8.8.88) against the Philadelphia Phillies, was rained out after 3 ½ innings. The first official night game was completed the next night, when the Cubs defeated the New York Mets, 6-4.

2014 = The Illinois Supreme Court launched its “Riding the Circuit” program in 2014. This initiative involves the Court occasionally holding oral arguments outside of Springfield to raise awareness about the judicial branch and to emphasize the crucial role the Court plays in interpreting state laws. Since the program began, the Court has met in various locations around the state: Ottawa in 2014, Lisle in 2016, Urbana Champaign in 2018, Godfrey in 2019, Chicago State University in 2019, and Northern Illinois University in DeKalb in 2024. During these sessions, the Court typically hears oral arguments in two cases—one criminal and one civil. Each case is allotted 50 minutes: 20 minutes for the appellant (the party appealing the case), 20 minutes to the appellee (the party defending the appeal), and 10 minutes for the appellant’s rebuttal. These events generally attract audiences of 500 to 750 people, including members of the legal profession, faculty, staff and students from the host institution, media, and the public. A significant portion of the audience consists of local high school students, who are invited to attend to gain a better understanding of state civics and the judicial branch. Prior to the oral arguments, local attorneys or judges visit high schools to brief students on the cases being heard and courtroom decorum. This exposure to the Supreme Court’s oral arguments has proven valuable for students studying civics, government, and history.

2020 = The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted daily life, and the Illinois Judicial Branch was no exception. Throughout the pandemic, Illinois remained open by transitioning many proceedings to remote hearings using video conferencing technology, such as Zoom. This shift allowed for greater party participation, reduced defaults and failures to appear, and improved case management and scheduling. Even after the pandemic subsided, remote hearings have continued to be a valuable tool for Illinois Courts. In May 2020, the Illinois Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments remotely. Since that time, all oral arguments have been livestreamed and archived, enhancing transparency and allowing viewers from around the world to engage with the Court’s work.

The Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission was created by the Supreme Court Historic Preservation Act in 2007 to assist and advise the Illinois Supreme Court in acquiring, collecting, preserving, and cataloging documents, artifacts, and information relating to the Illinois judiciary.

For more information or to schedule a guided tour email Samuel.Wheeler@illinoiscourthistory.org or call 217-670-0890 ext 4.